|

After a great deal of reading, synthesizing and analyzing, I found this perplexing comment by Moebius, jabbed at my mind as does a mosquito on a warm summer’s night. What does anyone see – young or old, when they open a picture book? How much and to what degree, do we naturally analyse a book’s content in terms of graphic images and text when we view a picture book for the very first time. This is indeed a difficult question to answer – of which no one can really be certain. What we do know, is that brain cognition is highly stimulated by colour and that individuals who are artistically inclined or exposed to the arts - at an early age, respond better in education than does a child who is not. We are told to limit the use of colour and design in a school classroom for those children with ADHD or more serious neurological disorders; hospitals are encouraged to use blues and pastel colours in children’s wards to stimulate the body’s healing processes; books are primarily published in colour, up until the end of primary schooling; prisons avoid the use of hues and primary colours such as red, to diminish the occurrence of violence among inmates. To me, it is more than obvious, colour affects our brain patterns, much more than we could ever hope to imagine. “How much do you see?” (Moebius, 1990: p138) When picture books are written, illustrated and published for the child’s market, considering them as physical, tangible artifacts that children can experience through touch, sound, written and visual representation; as highly imaginative, creative, well-presented whole products; where all parts of the book have been considered, is paramount. Appropriate stimulus colour, line, design and treatment of illustration that complements: the size, feel, format and organisation of text - in and on the book; as well as the chosen form of book i.e. board book, soft cover, hard back, felt or material book, pop-up book, chunky tots book, musical picture books, read to you picture books - all need to be considered to impart the maximum, multi-sensory experience. A child’s attention span is considerably shorter than an adult’s. The duration is determined by the age and stage of a child’s intellectual and emotional development. Writers, illustrators and publishers must responsibly determine, feed and balance this critical development, according to the literature they produced – based on social norms, understandings, cultural and educational standards. One must be careful of ‘semic slippage’ (1990: 135) as coined in Moebius, “...a kind of plate tectonics of the picture book, where word and image constitute separate plates sliding and scraping along against each other,” where text and illustration are often conflicting or contradictory. When one views picture books such as ‘The Snowy Day’ by Keats or ‘Sunday Chutney’ by Blabey, one is conscious of the balance of elements: the careful saturation of tint and creative use of line in the former; and framed illustrations as in scrap-booking photos, in the latter. In both cases, line is naively represented, as a child would draw. The protagonist of each appears to have created both the visual and written representation, which adds to the interest, believably, impact and focus within the story. From the outset, the reader is immersed in the tale, has a familiar rapport with the protagonist and passionately believes what he is being told - due to the clever use and placement of text in and around the illustration, throughout the book. Both situations are realistic, relevant and relatable to the reader and quite reminiscent of my own childhood. I too wondered where the snow went, when I brought it home. The wordless design of Rogers’, ‘The Boy, the Bear, the Baron, the Bard, significantly contributes to the intertextuality of this pictorial literature. The reader has time to analyse the period, time and setting of the tale; the relevance of the soccer ball as it shows the passing of time; the clever placement of crows (representing death) that appear throughout the book and the storyteller’s embedded use of humour, as one is flung into days of Shakespeare. The reader is drawn to the busyness of the character’s activities, as the ball carries us through to the next page. One shares a sense of relief, but sadness knowing that the boy must say goodbye to his friend the bear. There is definitely more to this complex picture book, than meets the eye. Even the endpapers and peritextuals requires one to ponder the meaning and exceptional worth of this book.

Moebius, W. (1990). Introduction to Picturebook Codes words and image. In P. Hunt, Children's literature: the development of criticism (pp. 131 - 147). London: Routledge.

0 Comments

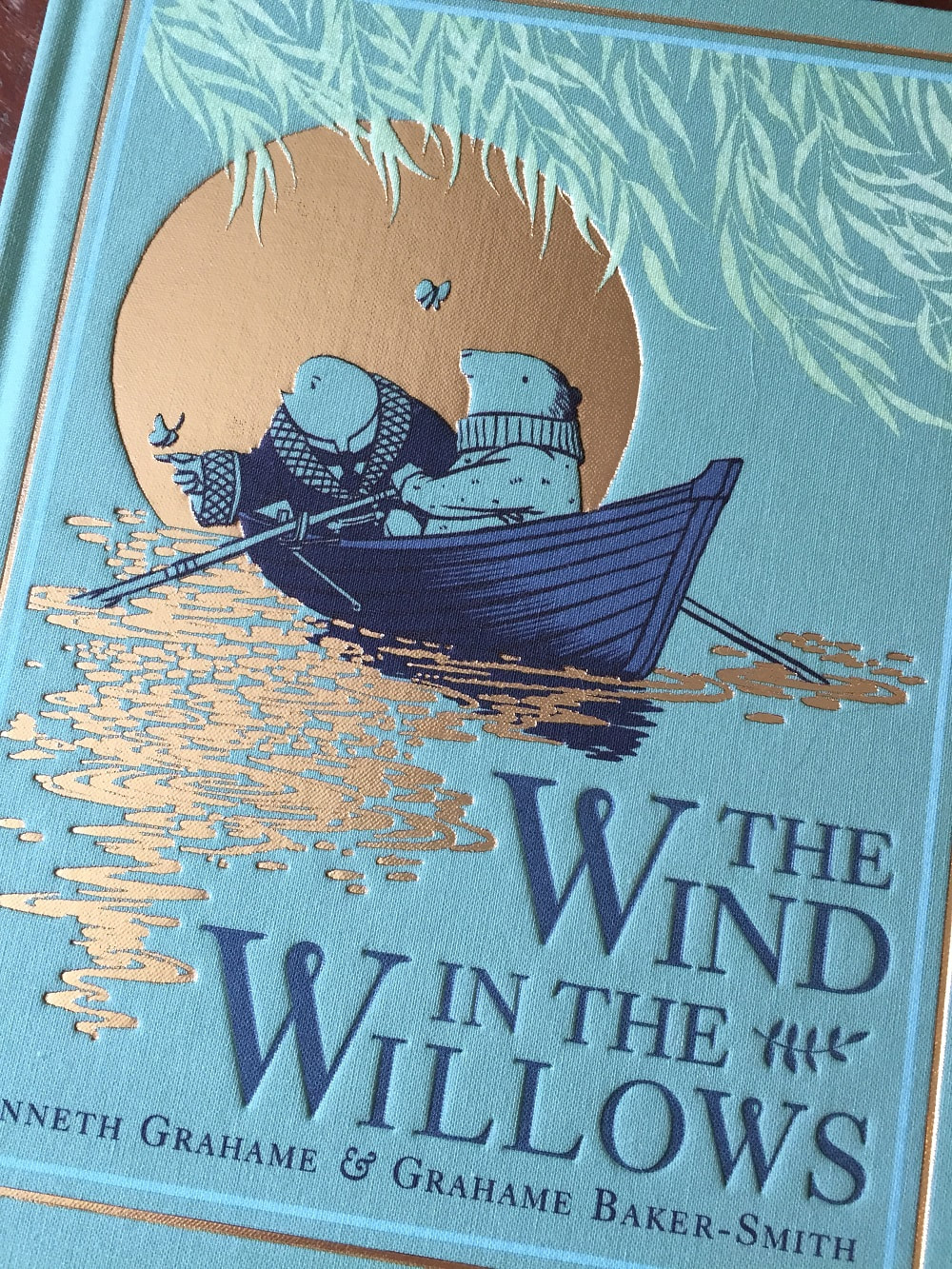

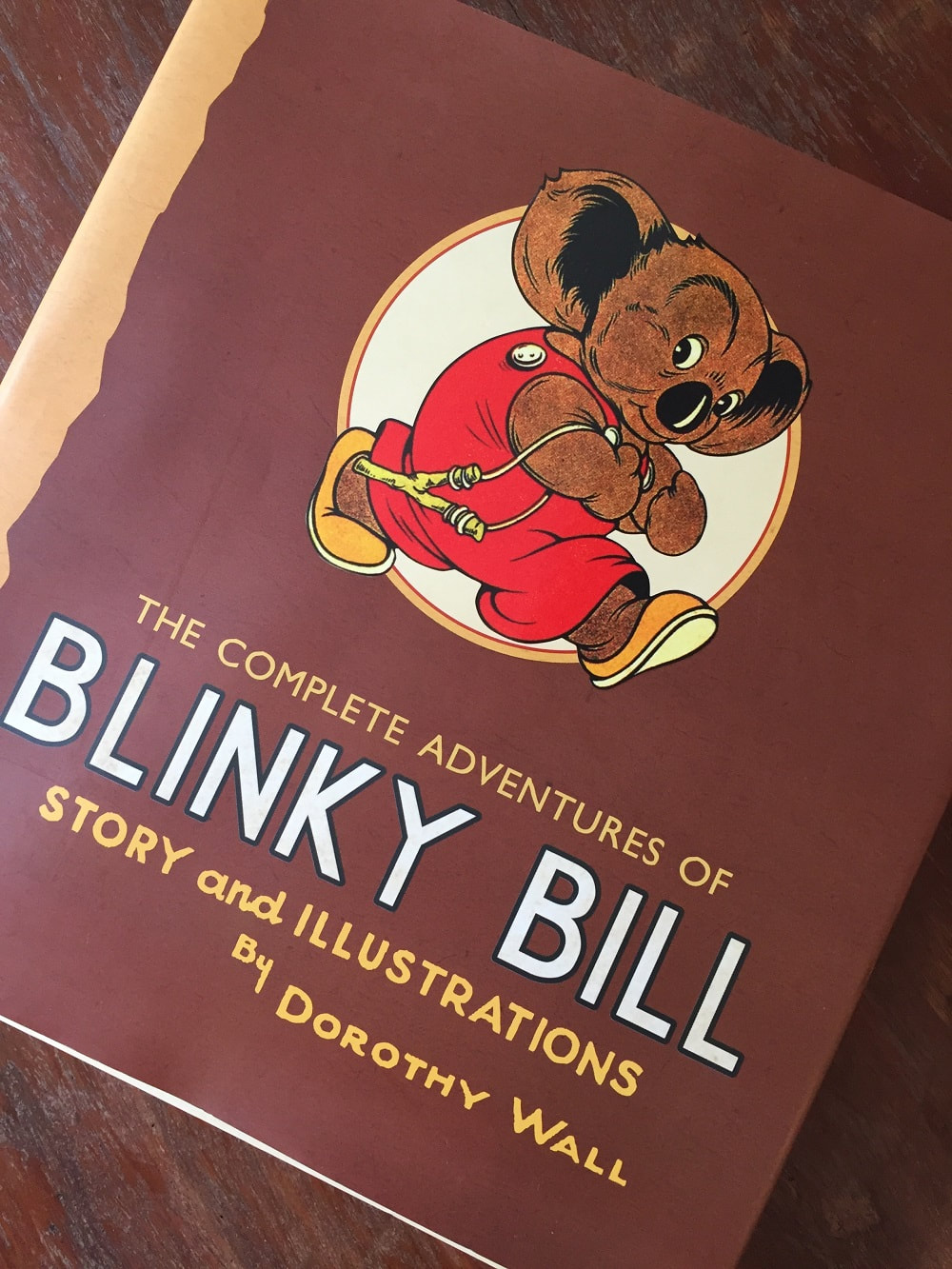

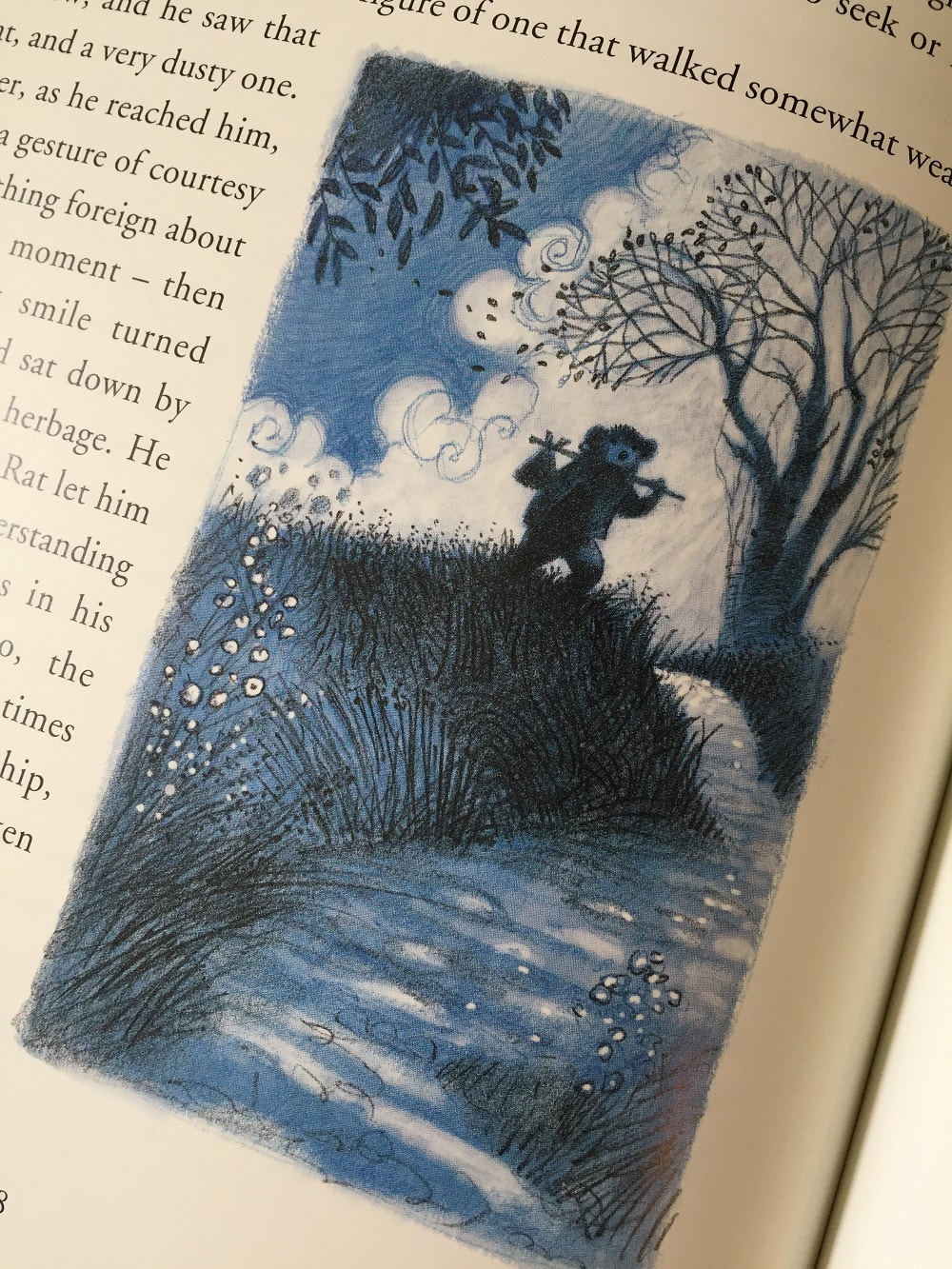

They say every writer is influenced by past lovers of literature, storytellers who made you think about the world and who ultimately brought about a similar love for putting down words on an empty sheet of paper. Two great books that did this for me was the Australian author and illustrator – Dorothy Wall and Scottish author – Kenneth Graham. The former wrote ‘The Adventures of Blinky Bill’, which I read on a religious basis upon going to bed and the latter ‘The Wind in the Willows’ that caused equally as much page turning and laughter. Both painted such vivid pictures of the characters’ daily escapades - so much so, I still pick up the books, year-after-year. Stepping back in time is always a great thing; it makes one smile, laugh and at times will bring one to tears. However, it was not just the writing that captured my imagination. The lively, black, pen and ink drawings of Blinky Bill and his friends and too, the beautiful, wispy watercolours seen in ‘The Wind in the Willows’ are images I still so easily recall. Dad and I would often sit down on my bed to discuss the illustrators’ ability to recreate those mind-stored visions, so easily on paper. Throughout my childhood, these were some of the books that allowed me to jump into the world of make believe – a very necessary place of existence for all children, as they grow up and quickly enter the world of stark reality. Escapism is the gift of all well-written tales and I am grateful to have had a book-learned, bookworm librarian for my father. Unfortunately, over the years my original books have suffered greatly with my constant moving from country to country. Upon seeing these delightfully-presented new editions, I could not help, but rock on over to the checkout to lay-down my pennies. As many of you know me well, it wasn’t just for me. Being a teacher - through and through, I love the idea of introducing something new, but classic to the classroom, at the beginning of the year. I’m always thinking of how I can capture the minds of my youngsters, to spur them on to enjoy the education process.

In today’s world, when picking up a physical book appears to be a burden, let alone reading one, I do my very best to impart my love of great literature by reading regularly to and with ‘my kids’, just like my dad did with me. You can pick up these new editions of two great classics, at every great bookstore – physical of course. ‘The Complete Adventures of Blinky Bill’ is put out by Angus and Robertson – an imprint of Harper Collins Children’s Books. This edition of ‘The Wind in the Willows’, illustrated by Graham Baker-Smith is published by Templar Books. And… need I say, ‘Both these books belong on your bookshelf for easy, family nightly-access.

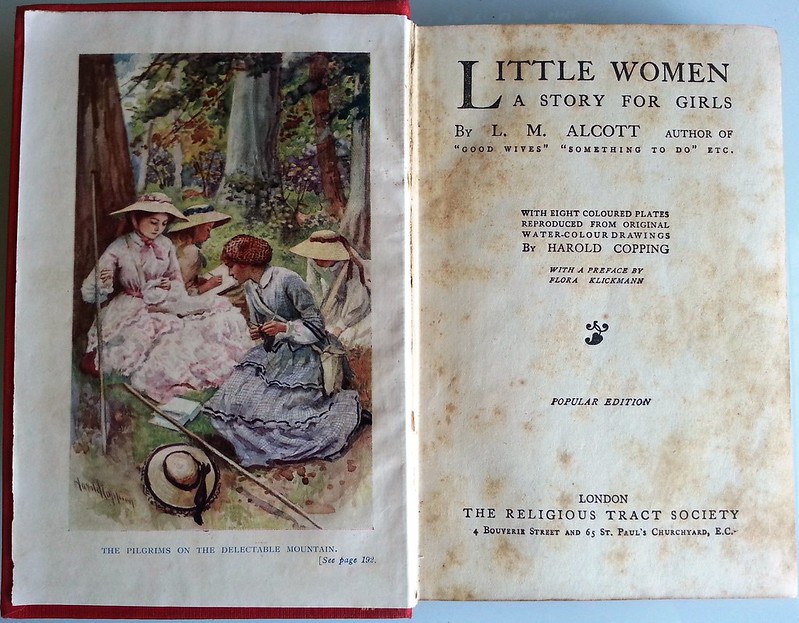

Toward the small, second story theatre of ‘The Strand’, I made my way up the winding stairs to take up a seat, for the long awaited film - ‘Little Women’ by Greta Gerwig. I am particularly aware of Louisa May Alcott’s original books, having read them back to front on several occasions as a child. Being such an acclaimed piece of historical literature and a very valid one in today’s male-dominated world – I expected to see many more persons, than a grand total of - six. Anyhow…

The December launch of Little Women that we manage to receive in the Southern Hemisphere - three months after the event, has very much peaked my interest. As the shorts begin, I am reminded that this female-directed piece by Gerwig, somehow managed to be snubbed by the Academy, even though nominated in four classes. However, Jacqueline Duncan did take out an Oscar for Best Costume Design – but that was the extent of it.

Filmed in the historical sites of Massachusetts, where the fictional characters of the March family lived – ‘Jo’ is played by Saoirse Ronan; ‘Meg’ by Emma Watson; ‘Amy by Florence Pugh; ‘Beth’ by Eliza Scalan; Laurie by Timoth’ee Chalamet; ‘Marmee’ played by Laura Dern and ‘Great Aunt March’ played by the seasoned actress - Meryl Streep. These dominant characters worked side by side ‘Mr Laurence’ played by Chris Cooper; Freiderich Bhaer by Louis Garrel; ‘Mr Dashwood’ by Tracey Letts; ‘Father March’ by Bob Odenkirk and ‘John Brooke’ played by James Norton. With such a fine cast of performers, it baffles me as to how this film managed not to score better than they did, at the Oscars.

The film opens with ‘Jo’ hightailing it into Volcano publishers to sell her story, because the family are short of funds. Under normal circumstances, stories sell for $25~$30, but she is forced to sell her story for only $20, given her female character - has not ‘followed the formula’. She is instructed by the editor that the story must be ‘short and spicy’ and if the main character is a girl - she must be either - married off or dead - by the end of the script, in order for it to sell.

Even at this early juncture in the film, I am forced to accept that female characters are disposable and play little importance in the great scheme of things. Following this directed evolution of understanding regarding the level of being, position of status and understanding that women must play lesser beings – the film moves forward in a similar vein to that of the originally published books by Alcott.

We see each of the actors, develop and grow into their unique characters – ‘Jo’ and ‘Meg’ take on the responsibility of working to support the family, while their father is off at war. ‘Jo’ who is a keen writer and very much the tomboy is: highly independent, often ill-spoken and intends to ‘make her own way in the world’. This manages to get her into strife with both family and friends as she writes and sells her stories as best she can, while she also reads regularly to Aunt March. ‘Jo’ constantly stresses that ‘women have minds as well as hearts and souls’ – ‘ambition as well as talent...’ ‘Meg’ is an entirely different kettle of fish. She is a budding actress, very much a traditionalist and takes on the job of teaching the nearby family of four. She also assumes a motherly approach to her siblings, while her mother is off attending to their father’s recovery – which annoys her siblings, no end.  Photo - Creative Commons Photo - Creative Commons

In this film, Amy’s artistic character - who longs for elegance and high society is used to deliver messages to the audience that a woman’s role is to be seen and not heard; anything vaguely resembling a thought process, is frowned upon. She is dissuaded from pursuing her studies of fine art in France – both by Great Aunt March who now insists she is the family’s ‘only hope’ for survival and by her self-realisation that pursuing the arts would entomb her to a life of poverty. Amy delivers carefully crafted lines to Laurie when he first attempts to take her hand in marriage because ‘Jo’ has refused him. She too want’s to be ‘great or nothing’, but she is distinctly aware that for a woman - marriage is an ‘economic proposition’. She is there to prop up a man, bear children under his name alone and is unable to make ‘means of her own’. Hence, Amy learns to play by the rules in order to get ahead in life. She states, ‘One of us must marry well’ – ‘I won’t be a commonplace dauber’.

For the youngest of the family – Beth March – life is short lived, but her message to embrace life for what it is; to appreciate all that is given and to return that gift of giving to those less fortunate, is important. She is the peace maker and pianist in this tale and shares her gift of caring for others openly. One can not help, but love her for what she represents in mankind. She delivers hope, understanding and a quiet admission that each and everyone of us needs to be ‘seen and heard’, in some manner or another. She is the energy that gives ‘Jo’ her reason to write; ‘Meg’ her reason to love and forgo her acting career; and ‘Amy’ her reason to seek comfort in the smaller things of life. Her love of music, calmly bonds the family beyond death. The family easily reminisce whenFreiderich Bhaer comes to visit for ‘Jo’, but takes time out to play Beth’s gifted piano from Mr. Laurence. Time stands still, as the family are reminded of Beth and her quiet, unassuming soul.  Photo - Creative Commons Photo - Creative Commons

Great Aunt March played by Meryl Streep reminds us all that as women, we must compromise and so often forgo our dreams in order to get ahead. She represents the monarch of the family – wise by seasoned existence, bitter at seeing the world the way it is and unforgiving to those who can not see the writing on the wall. Even young ‘Jo’, who is so independent to live life on her own terms; who states, ‘if I’m going to sell my heroine into marriage for money, I might as well get some of it’; eventually sees the light and chases after a male – despite being sick and tired of hearing that women were only good for love and love alone. It seems ironic that Gerwig’s film ends on such an anti-climax whereby we expect the heroine to find her man. Needless-to-say, we expect the March family to live happily ever after, but do they? Will they not want to seek andpush the boundaries of what is expected for a female? Will they be content to remain wall flowers?

|

Thoughts from

|

Publish with ELK Publishing |

Top Menu

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed